Please Mind the Gap: Identifying Control Gaps in ICFR

Tourists the world over love to visit London and ride the Tube, always listening for the famous expression, “Please mind the gap” (with that terrific British accent, of course). The announcer on the train says it specifically because, indeed, there is a gap between the train and the platform and for the unaware pedestrian, a foot through the gap could result in any number of possible injuries and damages.

Much like the Tube in London, a control gap can be a dangerous thing. While auditors and accountants don’t usually risk losing a limb, a control gap on the other hand could be an undiscovered material weakness which could allow for a potential material misstatement which could result in any number of possible damages to the public sector.

Control gaps are hard to identify, but they matter significantly. Almost twenty years after the implementation of SOX, it’s become easy for auditors to test internal controls that are in scope (i.e. that which we see). But what if the issuer doesn’t have a control in place to cover a potential material risk? Or what if the auditor did not scope in an important control to cover a material relevant assertion? It is much harder to identify a problem we cannot see, or, in other words, a gap.

Often, the focus of controls testing is on evaluating the design and operating effectiveness of internal controls. In fact, many of the PCAOB’s recurring findings surround firms’ failures to sufficiently test the design and operating effectiveness of controls, such as management review controls (MRCs). What is perhaps less well known is that the PCAOB also takes issue with engagement teams’ identification of controls to address deficiencies. In its Staff Preview of 2018 Inspection Observations which details recurring deficiencies, the PCAOB noted, “Auditors did not select controls for testing that address the specific risks of material misstatement.” Similarly, in its 2019 observations, the PCAOB said, “Auditors did not identify and test controls that sufficiently addressed the risks of material misstatement related to relevant assertions of certain significant accounts.” These issues translate into control gaps.

If you read through the auditing standards, specifically AS 2201, An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That is Integrated with an Audit of Financial Statements, you’ll notice that there is actually very little guidance around testing the design and operating effectiveness of internal controls. In fact, the first 41 paragraphs of AS 2201 (and for context, there are 98 paragraphs, not including the appendices) deal with planning the audit, understanding risk assessment, incorporating materiality, understanding the control environment, scoping significant accounts and assertions, understanding likely sources of potential misstatement, and finally, selecting controls to test. Almost half of the standard provides guidance to help auditors identify and select controls to address risks of material misstatement. Then, the PCAOB provides four paragraphs (AS 2201.42-.45) that speak to testing the design and operating effectiveness of controls. WOW! 41 paragraphs to ensure auditors select the appropriate controls and only four paragraphs to ensure auditors appropriately test controls.

In my experience with teams, a majority of the time and energy is spent on testing internal controls and very little time is spent on analyzing the controls in scope. In fact, most teams I know often take the “same as last year” approach without critically re-assessing the relevant risks and assertions, the likely sources of potential misstatement and selecting the right controls to address those risks. Control gaps are significant and can just as easily amount to a material weakness as can an ineffective control, whether due to design or operating effectiveness.

Given the significance of first identifying the appropriate controls and then testing those controls, consider the following:

Data lineage and process flows

The industry knows the importance of walkthroughs, but I have come to find that they are narrow in scope and often have become “perfunctory.” Many teams simply perform a walkthrough to understand the design of a control. But a walkthrough is actually intended to walk through a transaction from start to finish; in other words, to walk through the entire process. As controls occur (in the process), then yes, the engagement team should ask more clarifying questions to understand and evaluate the design of the specific control, but transactions don’t necessarily go from control to control. There is a process flow and teams need to understand that process in its entirety. I often advocate for the use of flow charts. If the client doesn’t have them, then the engagement team should consider creating a flow chart to help navigate the walkthrough. At each step in the process, the engagement team should ask, “what happens next?” – not, “what’s the next control?” A flow chart should map this exactly, allowing the engagement team to more easily identify potential control gaps.

While more often used in the IT realm, there’s an important concept of data lineage. It is vital that engagement teams understand the flow of data starting with where it originates and where it ends up (i.e. eventually the general ledger).

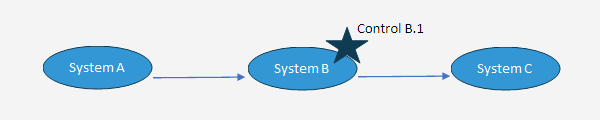

For instance, data that flows through multiple systems (Systems A, B and C) will need to have controls to ensure the complete and accurate transfer of information from system to system. If the engagement team only performs a walkthrough of a specific control (Control B.1), then the engagement team may conclude that the Control B.1 is appropriately designed. But without a walkthrough of the entire process, the engagement team may miss the fact that the data originates in System A and thus may need an “input control” and may also need an interface control to ensure the complete and accurate transfer of data between System A and B. In addition, without a walkthrough of the entire process, the engagement team may miss the fact that there needs to be a control to govern the complete and accurate transfer of data between System B and System C (which happens after Control B.1). These would all be control gaps that could jeopardize the relevant assertions of the account and result in a material weakness.

Especially today, given the integration of IT systems and automation, it is important for engagement teams to perform walkthroughs of entire processes with both financial statement and IT auditors.

Risk matrices

Most issuers have risk and control matrices. These matrices can be burdensome given the size and amount of information included within. I encourage teams to create a simpler version on their own; these simplified matrices can be the most effective method for mapping significant accounts, risks, and likely sources of potential misstatement (also referred to as “what could go wrong” or WCGW) to specific controls. Each account will have relevant assertions. Each relevant assertion will have multiple WCGWs. And each WCGW should have at least one control that specifically addresses that risk. Though usually completed by more junior team members, managers and partners should spend a significant amount time reviewing this matrix mapping since this is the foundation for the identification and scoping of controls.

Once scoped, it’s just a matter of testing the design and operating effectiveness. I realize that testing can take a significant amount of time as well, but generally speaking, the more time spent upfront planning an audit (including understanding and scoping controls), the better the execution of the audit.

Errors and exceptions

As we move into substantive testing, I encourage teams to consider errors and exceptions as these generally have control repercussions. Some errors may not be significant, such as reconciling differences between the subledger and GL due to rounding. A true error, however, often indicates a breakdown in controls. When teams find an error, consider whether the controls in place operated. If they in fact operated as designed, then either the controls are ineffectively designed or there is a control gap somewhere in the process that should address this error. Of course, take into account materiality; there may not be a risk of material misstatement, but the audit team should consider the effect of errors, the potential for material misstatement or material weakness, and document its judgments around these considerations.

Regarding exceptions, while engagement teams are quick to explain why exceptions are not errors, consider if there are control implications. For instance, in a substantive test over revenue occurrence, I’ve seen numerous tick marks explaining why there are no shipping documents (i.e. occurrence) for a specific selection. Maybe it’s because the this particular sale is actually a service and not a shipment. Okay, point noted; I’m not challenging the validity of the revenue. However, for this specific selection, the typical revenue recognition process is not applicable and that means the client should have controls designed and in place to ensure revenue recognition for this revenue stream is in accordance with accounting guidance. Did the client and did the engagement team identify a control to cover this “exception?” Regulators are keen to identify these types of situations for potential control gaps. Again, take into account materiality; to the extent this is an immaterial revenue stream, then perhaps no controls need to be identified and tested, but the engagement team should at least document its judgment.

When performing walkthroughs, I can’t emphasize enough the importance of asking control owners, “what happens when there’s an exception?” Or for automated processes, “is it possible to have a manual workaround?” These are potential exceptions that should have controls identified and operating to ensure there is no gap.

“Fresh” reviews

Finally, I encourage engagement teams to get “fresh” perspectives. While recurring year after year helps build a strong understanding of the client (which is critical to identifying potential control gaps), in an effort to drive efficiency, most audit approaches are simply rolled forward from the prior year. Thus, in lieu of re-assessing the risks and the in-scope controls meant to address the risks, teams simply adopt the prior year scoping.

Taking a step back though, is that really the most effective or appropriate action? The initial scoping of controls is often performed either a) upon client acceptance or b) upon initial SOX implementation.

- Client acceptance: In a first-year audit, regardless the size of the company, there is so much “learning” that occurs that it’s almost foolish to think that the scoping of controls made in the first year is the “best” or “most appropriate” scoping. Surely the engagement team will continue to learn and better understand a client over time and therefore identify additional controls that are needed to cover relevant risks.

- SOX implementation: Similarly, the first year of a SOX implementation is a huge undertaking. While the controls may cover the relevant risks at the time of implementation, there are often oversights that both management and auditors realize over time and thus controls will constantly be adapting. Layer onto this the fact that clients are perpetually changing, and it’s important to critically re-assess every year the scoping of controls.

To get fresh perspectives, consider the use of in-flight and lookback reviews or targeted ICFR gap analyses across clients to help engagement teams identify potential control gaps. It is important to have objective perspectives that can raise new insights about the scoping of controls.

And now back to London, the mere fact that there is such a large separation between the train and platform is possibly an indication that there was a control gap somewhere in the design and construction of the London Underground. I’m not sure who first identified the error, whether it was the engineers or an injured passenger, but clearly the London Tube is aware of the issue and has implemented a control to cover this risk and it goes: “Please mind the gap.”

About Johnson Global Advisory

Johnson Global partners with leadership of public accounting firms, driving change to achieve the highest level of audit quality. Led by former PCAOB and SEC staff, JGA professionals are passionate and practical in their support to firms in their audit quality journey. We accelerate the opportunities to improve quality through policies, practices, and controls throughout the firm. This innovative approach harnesses technology to transform audit quality. Our team is designed to maintain a close pulse on regulatory environments around the world and incorporate solutions which navigate those standards. JGA is committed to helping the profession in amplifying quality worldwide.

Visit www.johnson-global.com to learn more about Johnson Global.

Joe Lynch, JGA Shareholder, to Provide Insights on Changes to Engagement Quality Review Requirements