Internal Inspections - Part II: The Integral Inputs to Implementation

Last month, we began this three-part series on what makes an internal inspection program effective. Internal inspections are a critical part of the overall practice monitoring process and focus on specific engagement performance. We are passionate about this aspect of our clients’ systems of quality control (QC) because so much can be gleaned from the results. Consider all the aspects the program touches, such as client acceptance, independence, methodology, and consultations. Observations from the internal inspection program gives insight to the effectiveness of many elements within the firm's system of QC besides the engagement partner’s approval and issuance of the audit opinion.

In Part I of the series, A Deep Dive Into Design, JGA shared why an internal inspections program is important and what it should be achieving. We covered what we refer to as the Four P’s of designing an effective internal inspection process (The Point, The People, The Planning and The Procedures). In this article, let’s further build on that discussion and talk about execution.

Select the Engagements

Once the planning phase has been completed and the basic framework of the program has been established, you’re ready to determine how to apply the key criteria to select engagements for review. Whether it’s a risk-based, random, or coverage-based selection, the key criteria should be evaluated again to ensure no changes need to be made from the prior practice monitoring period. For example, if performing a pre-issuance review, did any changes in the environment, such as COVID-19, affect any issuers and should the firm consider that factor in its engagement selection process?

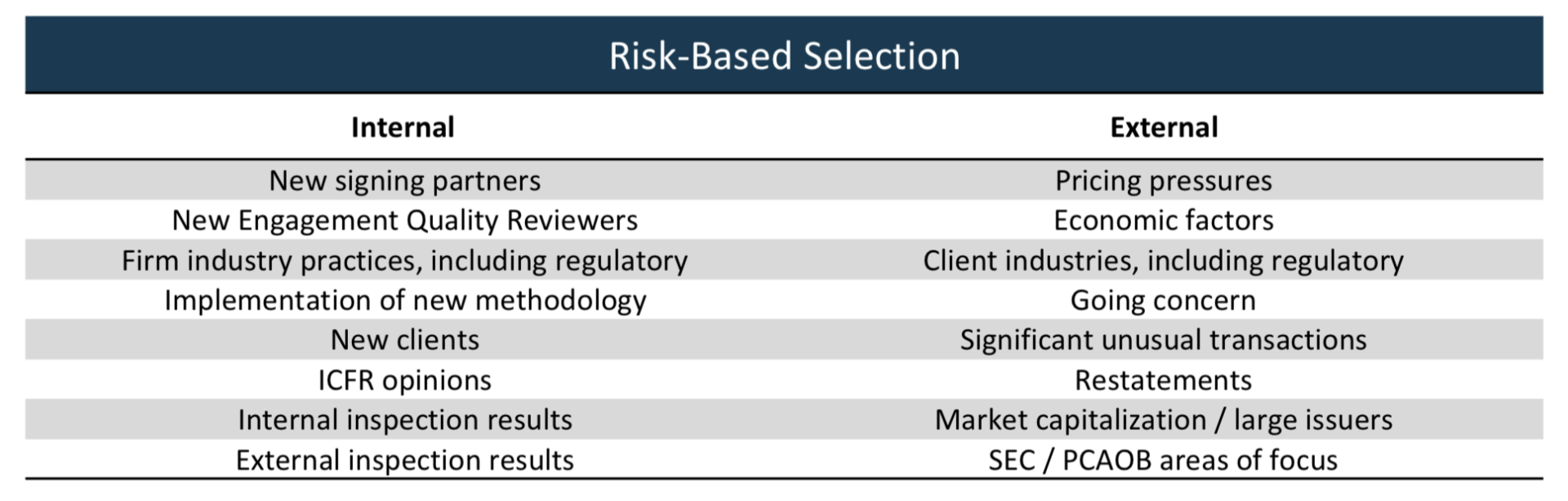

Risk-Based Selection

For the risk-based component of engagement selection, consider these factors.

Non-Risk-Based Selection

When we dig into our clients’ internal inspection programs with them, we always suggest they incorporate selection criteria that are non-risk-based.

These include:

- Partner coverage each period and over a span of multiple periods;

- Market cap of the assurance practice and/or regions or individual offices; and

- Some aspects of unpredictability such as random selection.

Assemble the Team

Consider these important elements of assembling and readying the right team for the most effective outcome.

Experience

Individuals and teams performing the inspections should have the appropriate experience. This includes technical accounting, auditing, and firm-specific experience. Often, we see that individuals may be audit experts but not necessarily technical accounting experts. That is perfectly fine, and we expect that a well-executed inspection is a team effort. Perhaps, similar to the audit environment, an inspection team should have the right resources in place to request consultations on important accounting matters identified during the inspection. An effective planning process includes identifying these specific risks in the audit and any technical individual(s) to add to the team. Outside consultants can also play an important role to handle aspects of the inspection that require specialized skills.

Independence

The internal inspection team should be independent, in fact and appearance, with the audit client during the period under audit and through the issuance of the internal inspection report. Procedures should be in place to ensure that only individuals that meet these requirements are assigned to an inspection. This includes individuals within firm leadership that have the ability to influence the results of the internal inspection program. We recommend that firms place a similar process around the planning of the inspection team to what is in place around obtaining representations and ensuring independence among the audit engagement team members while planning the audit.

Objectivity

Consider the individuals assigned to the team and whether they can stand their ground on a tough issue, even if it means there are deficiencies identified that rise to the level of an unsupported audit opinion. The pressure can be significant. Threats to that objectivity need to be addressed to ensure a fair and complete inspection. JGA considers various aspects of assignments that can pose risks to objectivity, including:

- reporting relationship;

- performance management incentives/disincentives of the individual(s) assigned to the inspection; and

- whether the results of that internal inspection can be subject to a second national office review for quality of the inspection procedures performed.

Clients and prospects come to us looking for ways to ensure there is an appropriate balance of objectivity in how their internal inspections are carried out. I believe when programs – and how they are executed – get stale, so does the objectivity and the results. While each firm has a unique set of circumstances, my general advice here is to consider changes to how inspections are assigned and how the inspection team members are evaluated. Incorporating elements of unpredictability is one way to keep inspection teams objective.

Prepare the Reviewers

Take time to prepare for the review. Inspectors assigned to an engagement should review information, including the financial statements, public filings, website, and firm information regarding the audit’s risk profile. Reviewers should begin the inspection with questions ready for the engagement team. Responses to preliminary questions from the engagement team before the review of the file help the reviewer confirm or redirect where to spend time in the file review.

Establish the Expectations

Why is it important?

The firm’s process should explain the importance of the program to engagement teams. Engagement partners facing an internal inspection should have a vested interest in the program’s success. While it’s counterintuitive for the partners going through a review, getting partners to think long-term about seeing the benefits of a strong program – and the opportunity costs of a weak program – will play a role in the program’s success. Overcoming any perceptions that an internal inspection is less important than an external inspection (such as a PCAOB inspection or AICPA peer review) will help identify problems before those other parties do.

How should it be conducted?

Reviewers should set daily or periodic touch points with the engagement team, depending on the size of the audit and length of review. Engagement teams should be expected to be responsive, thorough, and timely in addressing questions and concerns from the reviewers.

Regarding the manner of execution, we have found in our experience performing internal inspections and observing PCAOB inspections of our clients, that in-person inspections are more effective than inspections conducted remotely. While we can’t control the challenges that the pandemic has posed, we encourage firms to plan to get back to in-person interviews when it is safe to do so.

When should it be conducted?

The inspection of files should take place when engagement team members are available and can be focused. This means not during busy season and not when the subsequent year’s audit of the company selected for internal inspection is taking place. Generally, however, the sooner the better, so that observations made during the internal inspection can be incorporated into the subsequent audit’s planning process. From a firm-wide perspective, the sooner the inspections are completed the sooner firm leadership can design and implement policy changes to respond to thematic issues or other root causes associated with deficiencies.

Promote the Consistency

To fully interpret and respond to the firm-wide results of the practice monitoring review, it is critical to have a consistent application of the internal inspection procedures across engagements. A training program during the planning process and a thorough supervision and review function will ensure that inspectors stay objective and fair while also providing a complete review. When we evaluate or perform the outsourced internal inspection for a firm, we advise our clients that the partners, or those leading the review, should be involved at a sufficient level of detail to identify concerns or audit performance deficiencies. Training should provide examples to the reviewers to show just how deep those reviews should be.

While the process can seem painful, it could alternatively be a mutually-beneficial opportunity for the review team and the engagement team to learn with the shared goal of executing high-quality audits.

Whether firms are carrying out internal inspections as designed, or achieving the desired objectives of the program, is a whole new question. Next month we will discuss this aspect of monitoring effectiveness (or, the “monitoring of the monitoring” as coined in ISQM 1) as the final component in Part III of this series.

Jackson Johnson is president of Johnson Global Accountancy, a public accounting and consulting firm with clients throughout the world. He works directly with PCAOB-registered accounting firms and other firms to help them identify, develop, and implement opportunities to improve audit quality. Jackson also works with public and private companies on various technical accounting and transactional matters. His experience includes nearly six years with the PCAOB, where he worked with small and medium-sized accounting firms throughout the world, including foreign affiliates of large international accounting firms, in the areas of firm quality control and ICFR audits of financial statements. Prior to the PCAOB, Johnson worked with public and private clients in a variety of industries at Grant Thornton LLP in Boston, Los Angeles, and Hong Kong.

Bora Brock has over 20 years of experience in the accounting and auditing industry. At JGA, she works with firms of all sizes to improve and monitor audit quality. Primarily, she advises clients on root cause analysis, matters relating to independence, and evaluating and assisting with improvements to clients’ systems of quality control. Prior to working with JGA, she was an Associate Director in the Division of Registrations and Inspections at the PCAOB for 13 years conducting inspections of quality control and issuer audits. In addition, she played a leadership role in planning, executing and reporting on the annual inspections of a Global Network Firm, including, but not limited to, the oversight of inspections and quality control procedures, review of comment forms, development of the inspection report criticisms and quality control themes, and evaluation and review of firm remedial actions.

Johnson Global Advisory

1717 K Street NW, Suite 902

Washington, D.C. 20006

USA

+1 (702) 848-7084